Oriental freshwater mussels arose in East Gondwana and arrived to Asia on the Indian Plate and Burma Terrane | Scientific Reports - Nature.com

Abstract

Freshwater mussels cannot spread through oceanic barriers and represent a suitable model to test the continental drift patterns. Here, we reconstruct the diversification of Oriental freshwater mussels (Unionidae) and revise their taxonomy. We show that the Indian Subcontinent harbors a rather taxonomically poor fauna, containing 25 freshwater mussel species from one subfamily (Parreysiinae). This subfamily most likely originated in East Gondwana in the Jurassic and its representatives arrived to Asia on two Gondwanan fragments (Indian Plate and Burma Terrane). We propose that the Burma Terrane was connected with the Indian Plate through the Greater India up to the terminal Cretaceous. Later on, during the entire Paleogene epoch, these blocks have served as isolated evolutionary hotspots for freshwater mussels. The Burma Terrane collided with mainland Asia in the Late Eocene, leading to the origin of the Mekong's Indochinellini radiation. Our findings indicate that the Burma Terrane had played a major role as a Gondwanan "biotic ferry" alongside with the Indian Plate.

Introduction

Freshwater mussels (order Unionida) are a diverse and widespread group of large aquatic invertebrates1,2, providing a variety of ecosystem services3,4. These animals are highly sensitive to human impacts and climate changes5,6,7,8,9, revealing dramatically high rates of global decline and regional extinctions10,11. Natural dispersal of freshwater mussels mostly occurs at the larval stage together with their fish hosts, and usually requires direct connections between freshwater basins, because they are unable to cross oceanic barriers2,12,13,14,15. Hence, freshwater mussels are considered to be among the best model organisms for biogeographic and paleogeographic reconstructions16,17,18,19,20,21. Most freshwater mussel species are endemic to a certain faunal region, and multiple single-basin and intra-basin endemics do occur, especially in species-rich faunas such as those of Southeast Asia22,23,24,25,26,27,28, North America and Mesoamerica17,29,30, and tropical Africa31. Furthermore, even widespread species share some kind of phylogeographic structure throughout their continuous ranges, e.g. Anodonta anatina (Linnaeus, 1758) in Eurasia32,33 and Megalonaias nervosa (Rafinesque, 1820) in North America34.

Recently, freshwater mussels were used as a model group to perform an updated freshwater biogeographic division of South and Southeast Asia19,23,35. Based on the Unionidae phylogeny and endemism patterns, this area could be delineated to the Oriental, Sundaland, and East Asian freshwater biogeographic regions23. The Oriental Region contains two subregions, i.e. the Indian (Indian Subcontinent from the Indus Basin in Pakistan through Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka to the coastal basins of the Rakhine State of Myanmar) and Western Indochina (Myanmar from the Irrawaddy [Ayeyarwady] Basin to the Salween [Thanlwin], Tavoy [Dawei], and the Great Tenasserim [Tanintharyi] rivers) subregions23. A significant geographic barrier associated with the Indo-Burma Ranges in Western Myanmar and Northeastern India (Naga Hills, Chin Hills, and Rakhine Mountains) separates these entities23. The Sundaland Region covers the Mekong, Chao Phraya, and Mae Klong rivers, the drainages of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, and the Greater Sunda Islands23,28,35,36. Finally, the massive East Asian Region expands from coastal basins of Vietnam through eastern China, Korea, and Japan to the Russian Far East20,35,37.

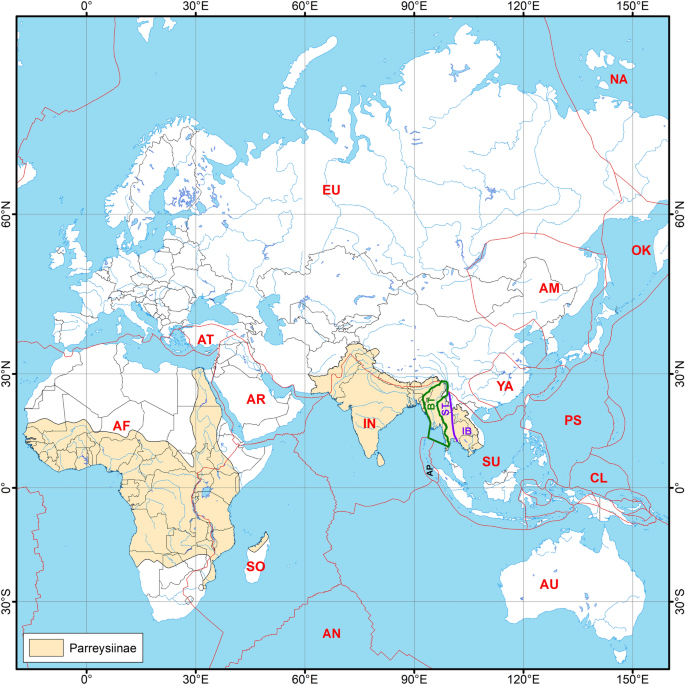

At first glance, the freshwater biogeographic division, outlined above, corresponds well to the boundaries of tectonic blocks such as the Indian Plate (Indian Subregion), Burma Terrane or West Burma Block (Western Indochina Subregion), and the Sunda Plate, containing the Indochina Block and Sibumasu Terrane (Sundaland Region)38,39,40,41 (Fig. 1). Dramatic tectonic movements during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic shaped the modern configuration of these blocks42,43. The Indian Plate was a part of East Gondwana and drifted northward as an insular landmass carrying Gondwanan biota39,44,45. Furthermore, the body of modern geological, tectonic, paleomagnetic, and paleontological research indicates that the Burma Terrane most likely represents a Gondwanan fragment that rafted to Asia together with the Indian Plate or as a part of a Trans-Tethyan island arc38,40,41,46,47,48,49,50. However, it is still unclear whether the continental drift could explain the biogeographic patterns in freshwater mussel distribution throughout the Oriental and Afrotropical regions and whether the disjunctive range of several Unionidae clades could reflect Mesozoic tectonic events19,31,51,52. While our knowledge on the taxonomy and evolutionary biogeography of freshwater mussels from tropical Africa, Western Indochina, and Sundaland has largely been improved during the last decade2,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,31,35,51,53,54,55,56, the Unionidae fauna of the Indian Subcontinent57,58 is still waiting for an integrative taxonomic research and thorough biogeographic modeling.

Global distribution of the subfamily Parreysiinae and tectonic plate boundaries. The subfamily range based on available published sources23,239 and our own data. The red lines indicate tectonic plate boundaries240. The red abbreviations indicate the names of larger tectonic plates: AF African; AM Amurian; AN Antarctic; AR Arabian; AT Anatolian; AU Australian; CL Caroline; IN Indian; NA North American; OK Okinawa; PS Philippine Sea Plate; SO Somalia; SU Sunda (with Indochina Block and Sibumasu Terrane); YA Yangtze. The boundaries of the Burma Terrane (BT), Sibumasu Terrane (ST), Indochina Block (IB), and the Andaman Platelet (AP) are given based on a series of modern tectonic works38,39,40. The Mogok–Mandalay–Mergui Belt40 is placed here within the boundary of the Burma Terrane. The map was created using ESRI ArcGIS 10 software (https://www.esri.com/arcgis). The topographic base of the map was created with Natural Earth Free Vector and Raster Map Data (https://www.naturalearthdata.com) and Global Self-consistent Hierarchical High-resolution Geography (https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/wessel/gshhg). (Map: Mikhail Yu. Gofarov).

This study (1) presents a taxonomic review of freshwater mussels from the Indian Subcontinent based on the most comprehensive morphological and DNA sequence datasets sampled to date; (2) reconstructs the origins, macroevolution patterns, and diversification of the Parreysiinae based on a multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny; and (3) postulates a novel hypothesis on a possible role of the Burma Terrane as a separate "biotic ferry" carrying a derivative of the Gondwanan biota to Asia through continental drift processes. Furthermore, we present a complete reappraisal of Mesozoic freshwater mussel species that were described from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds (Upper Cretaceous) on the Indian Subcontinent and an overview of a few doubtful and uncertain recent taxa that were linked to India.

Results

Freshwater mussel fauna of the Indian Subcontinent

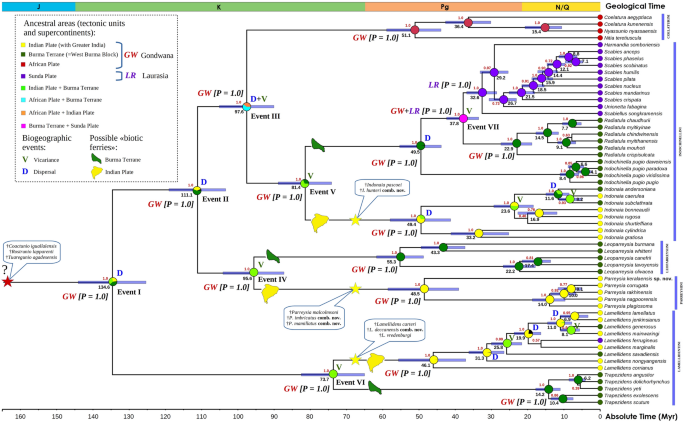

Here, we present the most comprehensive phylogenetic and distribution datasets on freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from the Indian Subcontinent sampled to date with supplement of related taxa from Indochina and Africa (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The phylogeny was reconstructed using partial sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), small ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA), and the nuclear large ribosomal RNA (28S rRNA) genes (Dataset 1). Based on the multi-locus phylogeny, DNA-based species delimitation procedures (Supplementary Fig. 2), and morphological data, we show that the Unionidae fauna of the Indian Subcontinent contains members of one subfamily, the Parreysiinae (Table 1). The total species richness of freshwater mussels on the Indian Subcontinent is rather uncertain due to the lack of DNA sequence data for multiple nominal taxa (Table 1). In summary, we propose a list of 25 valid species, almost all of which seem to be endemic to the subcontinent, though only 17 (68.0%) of those taxa were checked by means of a DNA-based approach. The 25 species recorded from the Indian Subcontinent belong to three tribes: Indochinellini (genus Indonaia Prashad, 1918: 8 species), Lamellidentini (genera Lamellidens Simpson, 1900 and Arcidopsis Simpson, 1900: 9 and 1 species, respectively), and Parreysiini (genus Parreysia Conrad, 1853: 6 species) (Figs. 3, 4 and 5)). One more genus, the monotypic Balwantia Prashad, 1919 (Fig. 5h), is considered here as Parreysiinae incertae sedis. The genera Arcidopsis, Balwantia, and Parreysia are endemic to the Indian Subcontinent, while each of the Indonaia and Lamellidens also contains three species from Western Indochina. Furthermore, there is one cementing bivalve species, Pseudomulleria dalyi (Smith, 1898) (Etheriidae), known to occur in India whose systematic assignment is still unclear (see "Discussion").

Time-calibrated phylogeny of the Parreysiinae based on the complete data set of mitochondrial and nuclear sequences (five partitions: three codons of COI + 16S rRNA + 28S rRNA). Events I-VII indicate a series of key biogeographic events, shaping the recent distribution of the subfamily (see "Results"). Nodal circle charts indicate the probabilities of certain ancestral areas based on the combined "tectonic plates" scenario (S-DIVA + DIVALIKE). The Sunda Plate contains the Indochina Block and Sibumasu Terrane39. Black color indicates an unexplained origin. Color symbols GW (Gondwana) and LR (Laurasia) indicate the results of the combined "supercontinents" scenario (S-DIVA + DIVALIKE) with the probabilities (P) of each ancestral area being given in square brackets. Stars at branches indicate reliable fossil record of the Mesozoic Parreysiinae in Africa (red) and India (yellow) with available fossil taxa being listed in the corresponding callouts. Taxonomic information on the Mesozoic fossil species from the Indian Subcontinent is given in Table 2. Red numbers near nodes are Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) values of BEAST v. 2.6.3. Black numbers near nodes are the mean node ages. Node bars are 95% HPD of divergence time. Time and biogeographic reconstructions for weakly supported nodes (BPP < 0.70) are not shown. Outgroup taxa are omitted. Stratigraphic chart according to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, 2021 (https://stratigraphy.org/chart).

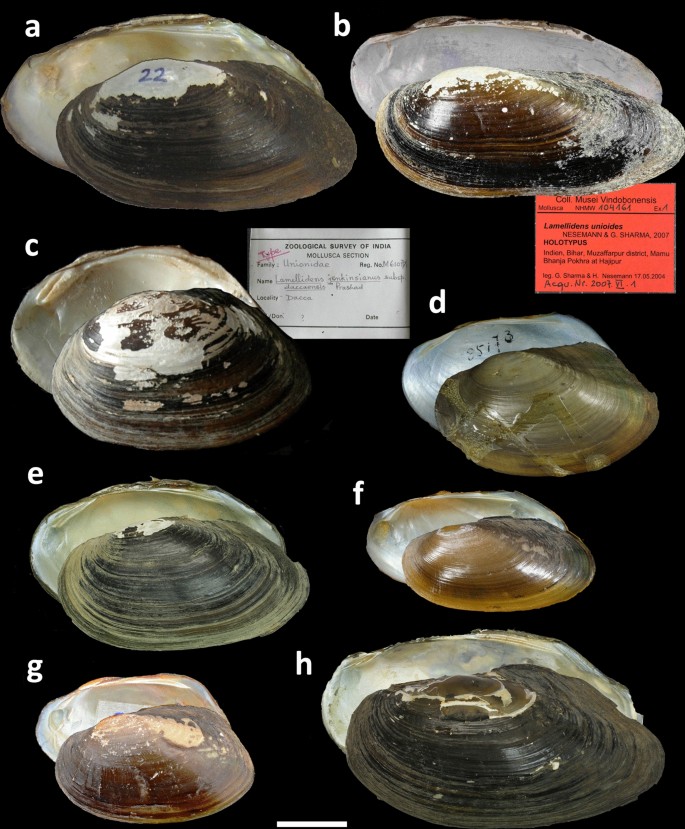

Shell examples of Lamellidens species from the Indian Subcontinent. (a) L. corrianus (Lea, 1834), Gokak, Gatprabha River, Krishna River basin, Western Ghats, Karnataka, India. (b) L. unioides Nesemann & Sharma in Nesemann et al., 2007, Bihar, Muzaffarpur District, Mamu Bhanja Pokhra at Hajipur, India (holotype NHMW 104161). (c) L. jenkinsianus (Benson, 1862), Dacca, Bangladesh (= Parreysia (s. str.) daccaensis Preston, 1912; holotype ZSI M6105/1). (d) L. lamellatus (Lea, 1838), Ganges River, India (holotype NMNH 85173). (e) L. mainwaringi Preston, 1912, Kaladan River, Myanmar (specimen RMBH biv153). (f) L. marginalis (Lamarck, 1819), brook at fish ponds, Hetauda, Ganges Basin, Narayani Zone, Central Region, Nepal (specimen SMF 348831/16.01). (g) L. marginalis (Lamarck, 1819), Krishna River, Nagarjuna Sagar, Telangana, India (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1227; specimen RLm3). (h) L. nongyangensis Preston, 1912 stat. rev., Lake of No Return [= Nongyang Lake], Irrawaddy Basin, Myanmar (topotype RMBH biv893/1). Scale bar = 20 mm. Photos: H. Singh, College of Fisheries, Ratnagiri, BOLD Systems BFB021-12, under a CC BY 3.0 license [a], N. V. Subba Rao and R. Pasupuleti [c, f, g], NMNH collection database under a CC0 1.0 license [d], A. Eschner [b], S. Hof [f], and E. S. Konopleva [e, h].

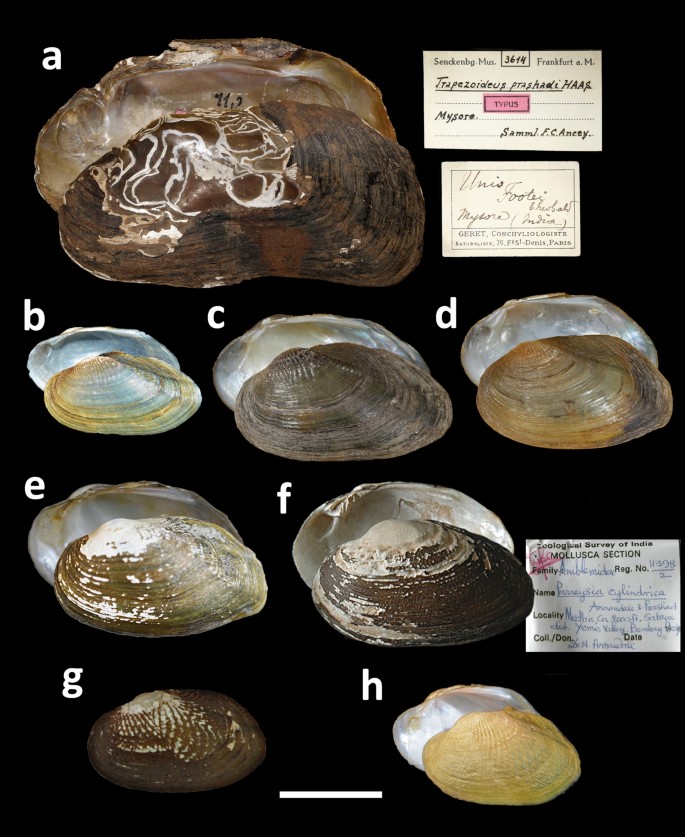

Shell examples of Arcidopsis and Indonaia species from the Indian Subcontinent. (a) A. footei (Theobald, 1876), Kistna flumine prope 'Gutparba falls' [Gokak Falls, Ghataprabna River, Krishna Basin, India] (= Trapezoideus prashadi Haas, 1922; holotype SMF 3614). (b) I. caerulea (Lea, 1831), fish pond, Krishna River basin, Uppalapadu, Andhra Pradesh, India (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1229; specimen RRc1). (c) I. caerulea (Lea, 1831), Jhajh nadi, Ganges basin, Narayani Zone, Central Region, Nepal (specimen SMF 348835/17.05). (d) I. gratiosa (Philippi, 1843) comb. nov., Jhajh nadi, Ganges Basin, Narayani Zone, Central Region, Nepal (specimen SMF 348834/17.15). (e) I. shurtleffiana (Lea, 1856), Godavari River, Nashik, Maharashtra, India (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1230; specimen RR3). (f) I. cylindrica (Annandale & Prashad, 1919) comb. nov., Yenna River, Upper Kistna watershed, at Medha, Krishna Basin, Maharashtra, India (syntype ZSI 11398/2). (g) I. cylindrica (Annandale & Prashad, 1919) comb. nov., Yenna River, Upper Kistna watershed, at Medha, Krishna Basin, Maharashtra, India (syntype ZSI 11398/2). (h) I. rugosa (Gmelin, 1791) comb. nov., Krishna River, Nagarjuna Sagar, Telangana, India (FBRC ZSI 1222; specimen RRl1). Scale bar = 20 mm. Photos: S. Hof [a, c-d], and N. V. Subba Rao and R. Pasupuleti [b, e, f, g, h].

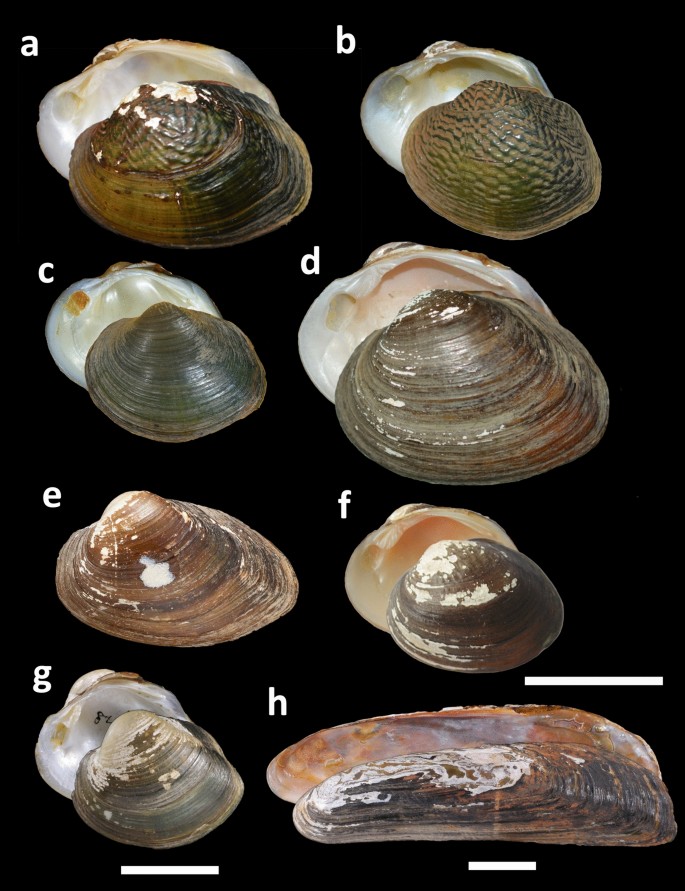

Shells of Parreysia and Balwantia species from the Indian Subcontinent. (a) P. keralaensis sp. nov., Periyar River, Aluva, Kerala, India (holotype FBRC ZSI 1007-a/RCB2). (b) P. keralaensis sp. nov., the type locality (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1007; paratype RCB3). (c) P. corrugata (Müller, 1774), brook at fish ponds, Hetauda, Ganges Basin, Narayani Zone, Central Region, Nepal (specimen SMF 348829/16.02). (d) P. corrugata (Müller, 1774). Krishna River, Nagarjuna Sagar, Telangana, India (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1224; specimen RPf1). (e) P. nagpoorensis (Lea, 1860), Ramganga River near Moradabad, Ganges Basin, Uttar Pradesh, India (= Unio pinax Benson, 1862: syntype UMZC I.105035.B241). (f) P. nagpoorensis (Lea, 1860), Krishna River, Nagarjuna Sagar, Telangana, India (museum lot FBRC ZSI 1224; specimen RPf2). (g) P. rajahensis (Lea, 1841). Rajah's Tank, India (holotype NMNH 84638). (h) B. soleniformis (Benson, 1836). Brahmaputra River, India (specimen NMNH 127246). Scale bar = 20 mm [a-e, g]; scale bar = 25 mm [f]; scale bar = 30 mm [h]. Photos: N. V. Subba Rao and R. Pasupuleti [a, b, d, f], S. Hof [c], K. Webb [e], and NMNH collection database under a CC0 1.0 license [g, h].

Macroevolution and evolutionary biogeography of the Parreysiinae

Our combined supercontinent-based biogeographic modeling (S-DIVA + DIVALIKE) reveals that this subfamily most likely originated and diversified on Gondwana and its fragments (probability = 1.00), with a secondary radiation of the so-called Mekong's Indochinellini (sensu Pfeiffer et al., 2018)51, a compact but diverse monophyletic subclade, in the Sundaland Subregion (probability = 1.00) (Fig. 2). The earliest split within the subfamily was associated with the separation of the Lamellidentini from other taxa by a dispersal event (probability = 1.00) and did occur in the Early Cretaceous (mean age = 135 Myr, 95% HPD = 125–144 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event I). Our combined tectonic plate-based ancestral area reconstruction (S-DIVA + DIVALIKE) suggests that this split occurred on the Burma Terrane, Indian Plate or on both of these blocks with equal probability (Fig. 2). The Parreysiini + Leoparreysiini clade most likely separated from the Coelaturini + Indochinellini clade by a dispersal event (probability = 1.00) in the mid-Cretaceous (mean age = 111 Myr, 95% HPD = 103–119 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event II). The Burma Terrane and Indian Plate are returned as the most probable ancestral areas during this event by our combined model (Fig. 2).

A series of vicariance events occurred in the Late Cretaceous: Coelaturini vs. Indochinellini (mean age = 98 Myr, 95% HPD = 90–105 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event III); Parreysiini vs. Leoparreysiini (mean age = 96 Myr, 95% HPD = 87–104 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event IV); Indonaia vs. the rest of the Indochinellini (mean age = 81 Myr, 95% HPD = 74–89 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event V); and Lamellidens vs. Trapezidens (mean age = 74 Myr, 95% HPD = 65–83 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event VI). The first vicariance event was preceded by a dispersal event and most likely corresponded to a split between Africa and Burma Terrane (probability = 0.60) or between Africa and Indian Plate (probability = 0.40). The other events in this series could be linked to repeated splits and reconnections between the Indian Plate and Burma Terrane (probability = 1.00).

The Mekong's Indochinellini did separate from the Radiatula clade near the terminal Eocene (mean age = 38 Myr, 95% HPD = 34–42 Myr) (Fig. 2: Event VII). Our ancestral area reconstruction suggests that this vicariance event could be linked to a direct connection between Burma Terrane and mainland Asia (probability = 1.00). Exchanges between freshwater mussel faunas of the Indian Plate and Burma Terrane, which traced well in Indonaia and Lamellidens radiations, started in the Late Oligocene (mean age = 24–26 Myr, 95% HPD = 18–30 Myr) and continued in the Late Miocene (mean age = 8 Myr, 95% HPD = 6–11 Myr) (Fig. 2). These vicariance events reflect direct connections (river captures) between freshwater systems of these terranes based on our combined biogeographic reconstruction (probability = 1.00 in almost all cases).

Taxonomy of freshwater mussels from the Indian Subcontinent

This taxonomic section is largely based on our novel phylogenetic and morphological research (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 1). A brief overview of the fauna is presented in Table 1, while the taxonomic account and explanatory comments for each species are given in the Supplementary Note 1. Additionally, one new species of the genus Parreysia from Southwestern India is described herein.

Family Unionidae Rafinesque, 1820.

Subfamily Parreysiinae Henderson, 1935.

Tribe Indochinellini Bolotov, Pfeiffer, Vikhrev & Konopleva, 2018.

Genus Indonaia Prashad, 1918.

Type species: Unio caeruleus Lea, 1831 (by original designation)59.

Distribution: Indian and Western Indochina subregions: from Indus River in Pakistan60 through India57,61, Bangladesh, Nepal61,62, and Bhutan63 to the Salween River in Myanmar56.

Comments: This genus contains not less than 11 recent species, eight of which occur on the Indian Subcontinent and three in the Western Indochina (Table 1 and Fig. 4b–h). Here, we tentatively delineate these taxa to three informal species groups (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The caerulea-group contains eight Radiatula-like species having an ovate or elongated shell of moderate thickness. The cylindrica-group joins two Parreysia-like species with a thicker, ovate shell. Finally, the involuta-group combines two peculiar species, sharing a thin, fragile shell. The pseudocardinal teeth in the latter group are lamellar, quite similar to those in Lamellidens taxa. The caerulea- and cylindrica-groups are largely supported by our phylogeny. The involuta-group was separated by means of a morphological approach alone, because the DNA sequences of both Indonaia involuta (Hanley, 1856) and I. olivaria (Lea, 1831) are not available. Based on the phylogenetic data, we transfer the nominal species Parreysia cylindrica Annandale & Prashad, 1919 to the genus Indonaia and propose I. cylindrica comb. nov. (Fig. 2, Fig. 4f–g, and Supplementary Figs. 1–2). Additionally, we revise the synonymy for nominal taxa in this genus (Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1). We chose not to discuss the nominal taxon Indonaia substriata (Lea, 1856) [= Nodularia (s. str.) pecten Preston, 1912]2 from Thailand here, because its generic placement and range are unclear and require future research efforts.

Two Late Cretaceous fossil species from the Intertrappean Beds of the Deccan Plateau in India are considered here as the earliest members of the Indonaia crown group, i.e. †I. hunteri (Hislop, 1860) comb. nov. and †I. pascoei Prashad, 1928 (Table 2 and Supplementary Note 2). Several younger fossil species in this genus were described from Miocene to Pliocene deposits (mostly the Siwalik Group64) in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Myanmar65,66,67,68,69.

Tribe Lamellidentini Modell, 1942.

Genus Arcidopsis Simpson, 1900.

Type species: Unio footei Theobald, 1876 (by original designation)70.

Distribution: Endemic to the upper section of the Krishna Basin in Western Ghats, India53,71. At first glance, historical records from "Mysore"72,73 could be linked to the Upper Kaveri Basin near the city of Mysuru53 but are more likely to be attributed to the former State of Mysore, which also covered part of the Upper Krishna Basin.

Comments: This monotypic genus with its single species, A. footei (Table 1 and and Fig. 4a), was placed within the Unionidae incertae sedis1,53 but later it was transferred to the Lamellidentini2. The DNA sequences of this taxon are yet to be generated, and its fossil records are unknown.

Genus Lamellidens Simpson, 1900 [= Velunio Haas, 1919 syn. nov.; type species: Unio velaris Sowerby, 1868 (by monotypy)74,75].

Type species: Unio marginalis Lamarck, 1819 (by original designation)70.

Distribution: Indian and Western Indochina subregions: widespread from Indus River in Pakistan60 through India, Sri Lanka57,61,76, Nepal61,62, Bhutan77, and Bangladesh57 to Salween River in Myanmar56 and southwestern Yunnan in China. Lamellidens candaharicus (Hutton, 1849) [= L. rhadinaeus Annandale & Prashad, 1919 syn. nov.], the westernmost species of this genus, was discovered from the endorheic Sistan/Helmand River drainage in eastern Iran and Afghanistan78.

Comments: This genus contains 12 recent species, nine of which occur on the Indian Subcontinent and three in the Western Indochina (Table 1 and Fig. 3a–h). In this study, we provisionally delineate these species to two informal groups, which are largely supported by our phylogenies (Supplementary Figs. 1–2, Fig. 2 and Table 1). The corrianus-group contains four species usually having a more or less elongated shell, while the marginalis-group joins species with somewhat ovate or rounded shell. Conversely, the shell outline itself cannot be used for diagnostic purposes even between the two species groups, as the shell shape of taxa in this genus is extremely variable, and multiple intermediate forms do occur, e.g. those in Lamellidens marginalis (Fig. 3f–g).

A new formal synonymy is proposed here for several nominal taxa (Table 1). Based on morphological and biogeographic data, we transfer the nominal taxon Physunio friersoni Simpson, 1914 [new name for Unio velaris Sowerby, 1868]79 to Lamellidens and propose L. friersoni (Simpson, 1914) comb. nov. Hence, Velunio Haas, 1919 syn. nov., a monotypic subgenus (section)75 of the genus Physunio Simpson, 1900, established for this taxon, should be considered a synonym of Lamellidens.

The nominal species Unio groenlandicus Mörch, 1868 was introduced based on a description and figure of Schröter80,81. This taxon cannot be attributed to Schröter81, because this author named it as "die breite Mahler-Muschel aus Grönland", which is not a binomial name. Mörch stated that it "is Unio testudinarius, Spgl. (U. marginalis, Lam.), a common shell from Tranquebar and other places in British East Indies"80. However, we cannot link Schröter's figure (pl. 9, Fig. 1)81 to a Lamellidens species due to the lack of pseudocardinal teeth. Hence, Unio groenlandicus is here considered a nomen dubium.

There are two older available names belonging to Lamellidens, i.e. Unio testudinarius Spengler, 1793 and U. truncatus Spengler, 1793 that were described from Tranquebar [Tharangambadi, 11.0292° N, 79.8494° E, Kaveri Basin, Tamil Nadu, India]82. Later, Haas redescribed these nominal taxa and illustrated the holotypes83. Based upon morphological examination, Haas considered Lamellidens testudinarius as the oldest available name for L. marginalis, and placed L. truncatus as a synonym of this species83,84. Furthermore, Haas synonymized the majority of nominal Lamellidens taxa under the name L. testudinarius84. However, this concept was largely ignored by subsequent researchers1,2,57. The assigment of these nominal taxa to certain species is not straghtforward. Morphologically, the holotype of Lamellidens testudinarius is an ovate shell83 that could be something from the marginalis-group, e.g. L. marginalis, L. mainwaringi or L. jenkinsianus. In its turn, the holotype of Lamellidens truncatus represents a narrower, elongated shell83 that looks either like L. corrianus or even the recently described L. unioides. Here, we prefer to consider these nominal species as taxa inquirenda but their identity will be clarified in the future based on molecular analyses of topotype samples from Tamil Nadu.

The three earliest fossil members of this genus were described from the Late Cretaceous Intertrappean Beds of the Deccan Plateau in India, i.e. †Lamellidens carteri (Hislop, 1860), †L. deccanensis (J. Sowerby in Malcolmson, 1840) comb. nov., and †L. vredenburgi Prashad, 1921 (Table 2 and Supplementary Note 2). There are several fossil species of Lamellidens from Miocene to Pliocene deposits (mostly the Siwalik Group64) in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Myanmar66,67,68,85.

Tribe Parreysiini Henderson, 1935.

Genus Parreysia Conrad, 1853.

Type species: Unio multidentatus Philippi, 1847 (by original designation)86.

Distribution: Indian Subregion: from Indus River in Pakistan60 through India, Sri Lanka57,61,76, Nepal61,62, and Bangladesh57 to coastal drainages of the Rakhine State of Myanmar23.

Comments: This genus contains six recent species endemic to the Indian Subcontinent (Table 1 and Fig. 5a–g). Here, we delineate these species to three informal groups (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The keralaensis-group contains Parreysia keralaensis sp. nov. only (Fig. 5a,b). This new species represents the most distant phylogenetic lineage within the genus (Fig. 2). The corrugata-group comprises four species that are phylogenetically and morphologically close to each other, representing a species complex (Table 1 and Fig. 5c–f). Our time-calibrated phylogeny indicates that the radiation within this group occurred during the Miocene (Fig. 2). Finally, the rajahensis-group contains a single species, Parreysia rajahensis (Lea, 1841). Although the DNA sequences of this species are not available, it probably represents a distant phylogenetic lineage due to a number of specific conchological features such as very thick, triangular shell and massive hinge plate (Fig. 5g).

The synonymy of Parreysia taxa is revised here (Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1). The nominal taxon Parreysia robsoni Frierson, 1927 [holotype NHMUK 1965150; type locality: Black River, North Carolina]87,88 cannot be linked to the Indian fauna, and it is considered here as a junior subjective synonym of Fusconaia masoni (Conrad, 1834) (Ambleminae) based on morphological features.

The three earliest fossil species belonging to this genus were discovered from the Late Cretaceous Intertrappean Beds of the Deccan Plateau in India, i.e. †Parreysia imbricatus (Hislop, 1860) comb. nov., †P. malcolmsoni (Hislop, 1860), and †P. mamillatus (Hislop, 1860) comb. nov. (Table 2 and Supplementary Note 2). There are several fossil species in this genus that were described from Miocene to Pliocene deposits (mostly the Siwalik Group64) in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Myanmar65,66,67,68,69.

Parreysia keralaensis Bolotov, Pasupuleti & Subba Rao sp. nov.

Figure 5a,b, Supplementary Figs. 3–6, Supplementary Table 2.

LSID: http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:627CB4BE-CD22-495A-8FDD-55F45D971CCD.

Type material: Holotype No. FBRC ZSI 1007-a (RCB2) [shell length 50.0 mm, shell height 33.5 mm, shell width 23.8 mm; reference COI sequence acc. no. KJ872811], Periyar River (downstream), 10.11° N, 76.37° E, Aluva, Kerala, India, 17.01.2014, R. Pasupuleti leg. Paratypes: Six specimens [museum lot No. FBRC ZSI 1007; specimen codes RCB3, RCB4, RCB5, RCB8, RCB9, and RCB12] from the type locality, 17.01.2014, R. Pasupuleti leg.; two specimens [museum lot No. FBRC ZSI 1006; specimen codes RNB1 and RNB2] from Periyar River (upstream), 10.06° N, 76.78° E, Neriamangalam, Kerala, India, 01.12.2014, R. Pasupuleti leg.; one specimen [museum lot No. FBRC ZSI 1223; specimen code RPC10] from Achankovil River, 9.25° N, 76.83° E, Pampa River basin, Kizhavalloor, Kerala, India, 03.09.2014, R. Pasupuleti leg. Reference COI sequences and shell measurements of the type series are given in Supplementary Table 2. The type series is deposited in FBRC ZSI (Hyderabad, Telangana, India).

Etymology: The new species name is dedicated to the Kerala State of India, in which it was collected.

Diagnosis: The new species can be distinguished from other Parreysia taxa by having a prominent, massive, rounded umbo and a specific wave-like sculpture over the umbo or through the entire shell surface (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, it represents the most distant phylogenetic lineage within the genus (Fig. 2).

Description: Medium-sized mussel: shell length 34.8–59.1 mm, shell height 23.7–38.2 mm, shell width 15.1–28.8 mm (N = 10; Supplementary Table 2). Shell thick, of triangular or rounded shape, slightly inequilateral; ventral margin slightly convex; dorsal, anterior, and posterior margins rounded. Umbo massive, prominent, elevated. Shell sculpture well developed, with specific wave-like ridges, covering the umbonal region or the entire shell. Most specimens share weak corrugate plications posteriorly. Periostracum brown to dark orange with green tinge. Nacre white, with yellowish or pinkish tinge, shining. Hinge plate rather narrow. Left valve with two curved lateral teeth and two strongly indented pseudocardinal teeth. Right valve with one curved lateral tooth and one massive, indented pseudocardinal tooth with a small auxiliary tooth. Anterior adductor scar rounded and deep, posterior adductor scar rounded and very shallow. Umbonal cavity very deep.

Distribution: Periyar and Pampa basins, Kerala, Southwestern India.

Parreysiinae incertae sedis.

Genus Balwantia Prashad, 1919.

Type species: Anodonta soleniformis Benson, 1836 (by original designation)89.

Distribution: Upper Brahmaputra and Upper Barak (Dhaleswari) basins, India89,90,91.

Comments: This monotypic genus (Table 1 and Fig. 5h) was long thought to be a synonym of Solenaia Conrad, 1869 based on a similar ultra-elongated shell shape1,57. The latter genus was recently revised with separation of several genera such as Solenaia s. str.27,92, Parvasolenaia Huang & Wu, 201993, Koreosolenaia Lee et al., 202037, and Sinosolenaia Bolotov et al., 202194. The first genus is a member of the tribe Contradentini27,92, while the others belong to the Gonideini37,93,94. Bolotov et al. restored Balwantia and placed B. soleniformis within the Contradentini together with two recently described species from Myanmar, having an ultra-elongated shell shape23. However, B. soleniformis shares unhooked glochidia and carries larvae in all the four gills (tetragenous brooding)89, and, hence, cannot be placed in the Contradentini27,95. Pfeiffer et al. considered it a monotypic genus, which may belong to the Parreysiinae27. Here, we place Balwantia as Parreysiinae incertae sedis because of the lack of available DNA sequences. Fossil records of this genus are not available.

Doubtful and uncertain freshwater mussel taxa linked to India

In this section, we present a morphology-based overview of several nominal taxa, which were described by Constantine S. Rafinesque96. Subsequent researchers largely ignored these taxa as "indeterminate Unionidae" and even as "the worthless fabrications of Rafinesque" because of very poor and incomplete descriptions97,98. In the body of available literature on the types of Unionidae described by Rafinesque99,100,101,102,103, any mention of the type series for his Indian taxa is absent. Furthermore, we were unable to locate the current whereabouts of these types neither in European museums nor in those in the USA (including the ANSP Malacology Collection database; http://clade.ansp.org/malacology/collections). Perhaps, the type lots have been sold to a private collector(s), because in the introduction of that paper Rafinesque offered for sale all the type shells described there96. Hence, the types are probably lost. Therefore, our decisions and comments are based exclusively on the original descriptions. Taxa, the protologues of which lack diagnostic features for reliable taxonomic identification, are considered here as nomina dubia.

A complete reappraisal of Rafinesque's nominal taxa linked to India96 is given in Supplementary Note 3, while a brief summary of our taxonomic decisions is presented here. Diplasma marginata Rafinesque, 1831 is considered a nomen dubium, because its type locality is uncertain (River Tennessee or Hindostan) and the identity is unclear. Three more nominal species cannot be identified with certainty based on the original descriptions and are also considered nomina dubia: Diplasma similis Rafinesque, 1831 (type locality: River Ganges); Diplasma (Hemisolasma) vitrea Rafinesque, 1831 (type locality: River Jellinghy in Bengal [approx. 23.4356° N, 88.4905° E, Jalangi River, West Bengal, India]); and Lampsilis fulgens Rafinesque, 1831 (type locality: River Ganges)96. Hence, the associated genus- and family-group names such as Diplasma Rafinesque, 1831 (type species: Diplasma marginata98), Hemisolasma Rafinesque, 1831 (type species: Diplasma (Hemisolasma) vitrea101,104), Diplasminae Modell, 1942105, and Hemisolasminae Starobogatov, 1970106 also become nomina dubia.

Based on the original descriptions96, Lampsilis argyratus Rafinesque, 1831 (type locality: River Ganges) and Diplasma (Hemisolasma) striata Rafinesque, 1831 (type locality: River Jellinghy in Bengal [approx. 23.4356° N, 88.4905° E, Jalangi River, West Bengal, India]) are considered here as junior synonyms of Indonaia caerulea (Lea, 1831) and I. rugosa (Gmelin, 1791) comb. nov., respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, the diagnostic features, mentioned in the protologue96, clearly indicate that the monotypic genus Loncosilla Rafinesque, 1831 with its type species Loncosilla solenoides Rafinesque, 1831 is not a unionid mussel but a freshwater clam of the family Pharidae. A more in-depth comparative analysis using available taxonomic works on freshwater Pharidae107,108 allowed us to propose the formal synonymy as follows: Novaculina Benson, 1830 [= Loncosilla Rafinesque, 1831 syn. nov.] and Novaculina gangetica Benson, 1830 [= Loncosilla solenoides Rafinesque, 1831 syn. nov.] (Pharidae: Pharellinae).

Additionally, we would note on the enigmatic nominal taxon Unio digitiformis Sowerby, 1868 [holotype NHMUK 1965199; type locality: India] that shares an ultra-elongated shell with pointed posterior margin. Different authors placed it within different genera such as Nodularia Conrad, 1853, Lanceolaria Conrad, 1853, and Indochinella Bolotov et al., 201835,84,109,110. Haas stated that this species is certainly not a member of the Indian fauna84. Based upon a morphological examination of the holotype, we found that it conchologically corresponds to Diplodon parallelopipedon (Lea, 1834) (Hyriidae: Hyriinae), a South American species, which is known to occur in the Paraná Basin and coastal drainages of Uruguay1,2. Hence, its type locality was given in error. The formal synonymy is proposed here as follows: Diplodon parallelopipedon [= Unio digitiformis Sowerby, 1868 syn. nov.].

Discussion

Taxonomic richness and endemism of Oriental freshwater mussels

The Indian Subcontinent houses a rather taxonomically poor fauna of the Unionidae, which contains 25 species belonging to three Gondwanan tribes (Indochinellini, Lamellidentini, and Parreysiini) and one subfamily, the Parreysiinae. All these species are endemic to the region, except for Lamellidens nongyangensis Preston, 1912, a local population of which was recorded in Lake of No Return (Nongyang Lake) near the boundary between India and Myanmar. Our novel results confirm the conclusion of Bolotov et al.19 that the Unionidae faunas of the Indian...

Comments

Post a Comment