Whale sharks are the world's biggest omnivores, scientists discover - Livescience.com

Whale sharks are the biggest shark species in the world, and now scientists have found that the giant sharks are even more prodigious eating machines than previously thought. In addition to gulping down enormous mouthfuls of krill — tiny shrimplike crustaceans — whale sharks also swallow huge helpings of seaweed, enabling the aquatic giants to officially dethrone Kodiak bears (Ursus arctos middendorffi) as the world's largest omnivores.

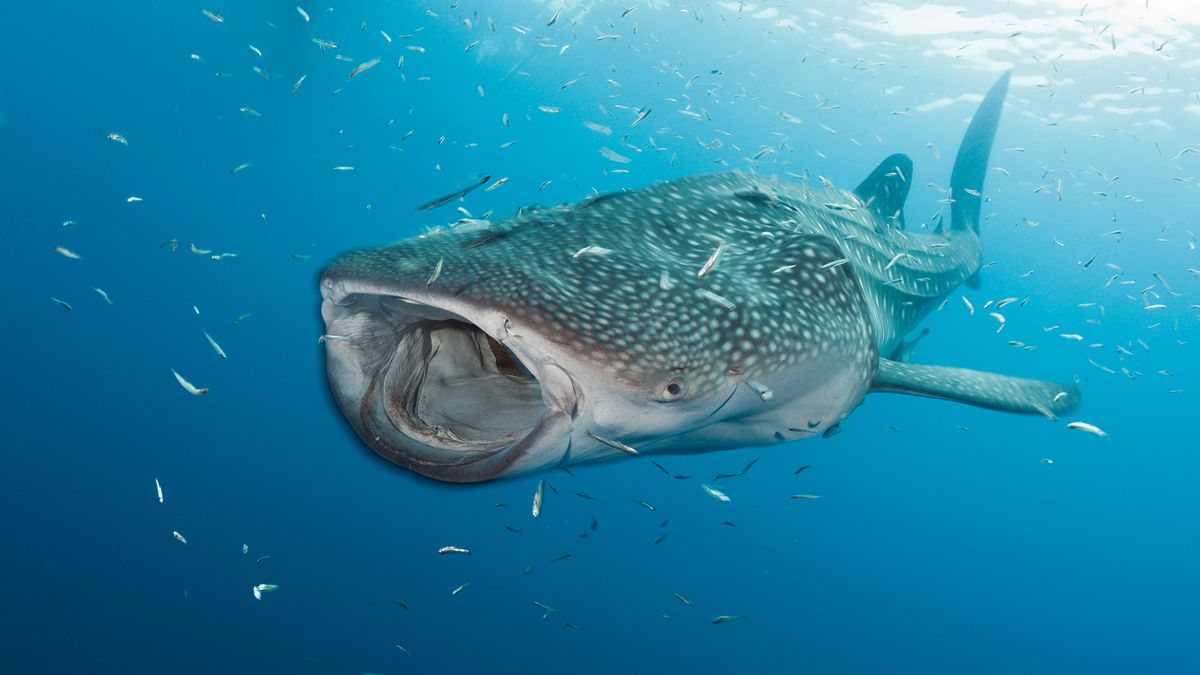

Researchers made the discovery by analyzing whale shark (Rhincodon typus) skin samples collected near Western Australia's Ningaloo reef. These gargantuan sharks are the largest fish in the sea, weighing up to 40 tons (36 metric tons) and growing to about 40 feet (12 meters) long on average, according to the National Ocean Service. Until now, scientists thought that the gentle giants were primarily filter feeders, gaping their cavernous mouths wide to gulp in roughly 21,200 cubic feet (600 cubic meters) of water every hour. Then, by straining the water out through their gills, the sharks are left with mouthfuls of plankton, shrimp, tiny fish and crustaceans to swallow down.

But the new discovery, published July 19 in the journal Ecology, has given scientists important new information to chew on.

Related: Stupendous sharks: The biggest, smallest and strangest sharks in the world

"This causes us to rethink everything we thought we knew about what whale sharks eat" and calls into question other aspects of the sharks' behavior "out in the open ocean," lead study author Mark Meekan, a fish biologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Queensland, said in a statement.

Meekan said that the discovery contradicts the common assumption that large land creatures are typically herbivores, but those that live in the sea occupy a different niche on the food chain, feeding on small shrimp and fish.

"Turns out that maybe the system of evolution on land and in the water isn't that different after all," Meekan said.

For their study, the scientists collected the sharks' possible food sources — ranging from tiny crustaceans and plankton to large clumps of seaweed — and then chemically analyzed the samples to reveal their amino and fatty acids. After cross-referencing these acids with those found in skin samples taken from whale sharks, the researchers identified high concentrations of sargassum — a type of brown seaweed made up of thousands of microscopic algae — in the sharks' diets.

The scientists think this omnivorous diet could be a result of the sharks evolving to digest accidentally swallowed seaweed, saving them the energy cost of spitting it back out.

"We think that over evolutionary time, whale sharks have evolved the ability to digest some of this sargassum that's going into their guts," Meekan said. "So, the vision we have of whale sharks coming to Ningaloo just to feast on these little krill is only half the story. They're actually out there eating a fair amount of algae too."

Having a broader range of food sources might sound like good news for whale sharks, as it could help them withstand potential upheavals to their marine ecosystems brought about by climate change. But the scientists said it's more complicated than that. It's possible that the sharks' propensity for swallowing most of what is swept into their mouths could make them far more likely to swallow copious amounts of ocean-borne plastics, according to the study.

"Whale sharks can pass some plastics through the gut," but ingesting small or large plastic pieces could cause the sharks to vomit up their meals, and could reduce their gut capacity and interfere with digestion, the researchers wrote.

For more Shark Week content, check out our handy streaming guide here.

Originally published on Live Science.

Comments

Post a Comment